Happy holidays!

This week I chose to unlock a paid post published back in August about how clearinghouses work. If you enjoy this post please consider subscribing to Front Month Premium, the paid portion of this newsletter where I dive into market structure topics like this. Thank you for your support!

I have a confession to make… I LOVE clearinghouses.

I don’t know what season of life you’d have to find yourself in for the inner workings of a clearinghouse to fill you with excitement, but that’s where I am. These peculiar systems are a prime example of why I wanted to create this newsletter.

Clearinghouses are really important - they help lower the cost of nearly every physical & financial product in existence. They’re complex - most people don’t really know how they work, even within the industry. Most importantly, I believe they’re criminally under-appreciated. Clearinghouses have been a primary driver of exchange success since the ‘08 financial crisis, and still form a critical & inseparable part of their businesses to this day.

I want to spend this post explaining the basics, a little bit of the science, and mainly the business of clearinghouses as they exist today. Exchange investors can use this knowledge to help separate important headlines from noise, better understand a company’s strategy, and spot new industry-wide trends as they emerge.

At the very least I think you’ll find them interesting. I certainly do.

The Basics

We’ll start with the important question - what is a clearinghouse?

Imagine you’re a big time commodities trader with a $100 million account. You think the price of oil will go way up over the next 6-12 months and want to profit from this theory. You can do one of two things:

You can call up a bank and buy a structured product - an energy swap - that allows you to profit from the price of oil going up. If your trade doesn’t work, you owe the bank money and vice versa. Let’s say that while your trade is open, the bank you called up goes bankrupt. Uh oh - your counterparty no longer has money to pay you back. This is called default risk or counterparty credit risk, and it’s real & worth respecting.

OR, you can connect to an energy exchange’s clearinghouse and buy an oil future from another trader on the exchange or a market maker. Just like with option #1, if your trade doesn’t work you owe your counterparty money & vice versa, but if they go bankrupt and can’t pay you back the clearinghouse will step in and pay you instead. You have an effective guarantee that no matter what happens, you will get paid if your trade works.

This idea of a payment guarantee is extremely powerful. It builds trust in connected markets & allows businesses to make similar guarantees to their customer base. Some examples:

In the 1980s McDonalds used a combination of grain & livestock futures, backed by the clearinghouse guarantee, to lock in volatile commodity costs & launch a new product - the Chicken McNugget.

Airlines use clearinghouse-supported futures products constantly to hedge the cost of jet fuel and offer competitive ticket prices to passengers.

Most parts of the supply chain for commodities like coffee, sugar, cocoa, & cotton use futures to lock in their respective profits. Cheap hedges combined with a clearinghouse guarantee allow that coffee bean to go from farm to processing plant to morning cup for as low a price as possible.

Without clearinghouses it would cost all of these businesses considerably more to take the risk of market volatility out of their operations, and it would almost certainly lead to higher prices for every major product or service. Clearinghouses provide a direct, tangible, powerful service to all parts of the global economy.

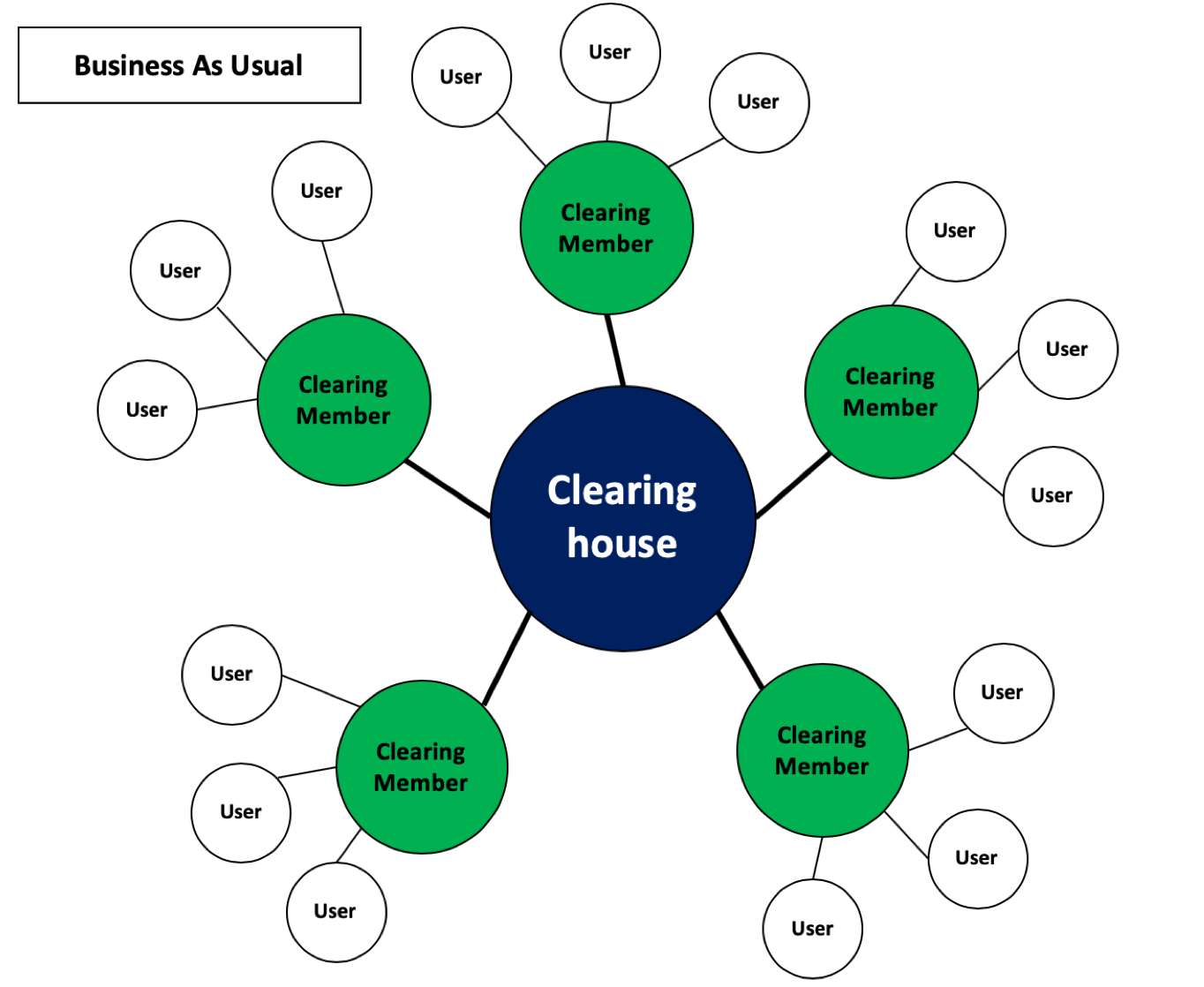

How is it possible for a clearinghouse to guarantee payment? The answer lies in its elegant design - clearinghouses insert themselves in the middle of a market & require all users to interact with & process trades through it. The result is a centralized network that resembles the below:

(Source: author rendering)

Most users don’t connect directly to the clearinghouse - they instead route through a clearing member, usually a broker or bank that gives money & legal power to the clearinghouse in exchange for access. Users post funds at the clearinghouse to cover their trade, called margin, which is normally a fraction of the total notional size of their position. These funds are centrally pooled, where gains & losses are transferred between users during the life of a trade. If I lose money on a futures trade & my initial margin deposit doesn’t cover the loss, the clearinghouse may require me to send it more money or risk default.

In addition to the pooled funds of all its users, clearinghouses hold extra levels of cash to further guarantee payment in the event of unexpected losses. For example, CME makes public the amount of cash available in its clearinghouse at any one time, split into segregated tranches:

Clearing Member Funds - if a user suffers losses they can’t pay for, the first entity in charge of covering the loss is the clearing member. If the member has funds to cover the loss it can isolate the event & prevent it from affecting the rest of the clearinghouse network.

Exchange Contribution - CME keeps its own emergency cash on deposit to cover potential losses the clearing member can’t. As of Q1 2021 this amount stood at $100 million.

Guaranty Fund - All clearing members who connect to CME are required to park their own emergency funds into this account. If the Guaranty Fund were ever used or exhausted, members would be required to refill it to stay in good standing. As of Q1 CME’s Guaranty Fund had ~$5 billion of capital.

Assessment Powers - If it ever came to it, CME has the power to call on its members to supply additional funds to keep the clearinghouse solvent. The maximum amount that CME could in theory require from its members is ~$13 billion.

Combine this with the ~$180 billion of user margin funds on deposit, and it would take an event resulting in over $200 billion of losses in a short period of time to cause CME’s clearinghouse to collapse. The odds of this happening are extremely small. This $200 billion is what underpins the clearinghouse’s payment guarantee.

Instances of clearinghouses actually collapsing are few & far between, but they do exist. Hong Kong’s futures clearinghouse collapsed in the crash of 1987 when billionaire Robert Ng refused to pay over $200 million in losses and colluded with his brokers to avoid posting margin. More recently, Nasdaq’s European clearinghouse nearly collapsed in 2018 when a Norwegian power trader lost $133 million in Scandinavian electricity futures, forcing clearing members to refill emergency Guaranty Funds or risk default themselves. These events notably came among small, mostly regional clearing units rather than the global behemoths like CME, ICE or LSE, but they are worth understanding.

Black Friday Sale!

Between now and December 4 I’m offering a 20% discount on annual subscriptions to Front Month Premium. Subscribe below and get immediate access to a deep archive of professional level market structure research & analysis. Join banks, exchanges & HFT firms around the world who’ve already signed up for the lowest available price.

The Science

Put yourself back in the shoes of that $100 million energy trader who thinks oil’s about to rise in price. You have a 6 month time horizon for your trade, so you look at CME WTI futures contracts out to February 2022. A 1,000 barrel futures contract trades at ~$66 per barrel, for a total value of $66,000. You decide to buy 10 contracts representing $660,000 exposure to oil’s price. When you go to send your money to the clearinghouse, however, you realize you only have to put up $49,500 of initial margin, or 7% of the total position. Why?

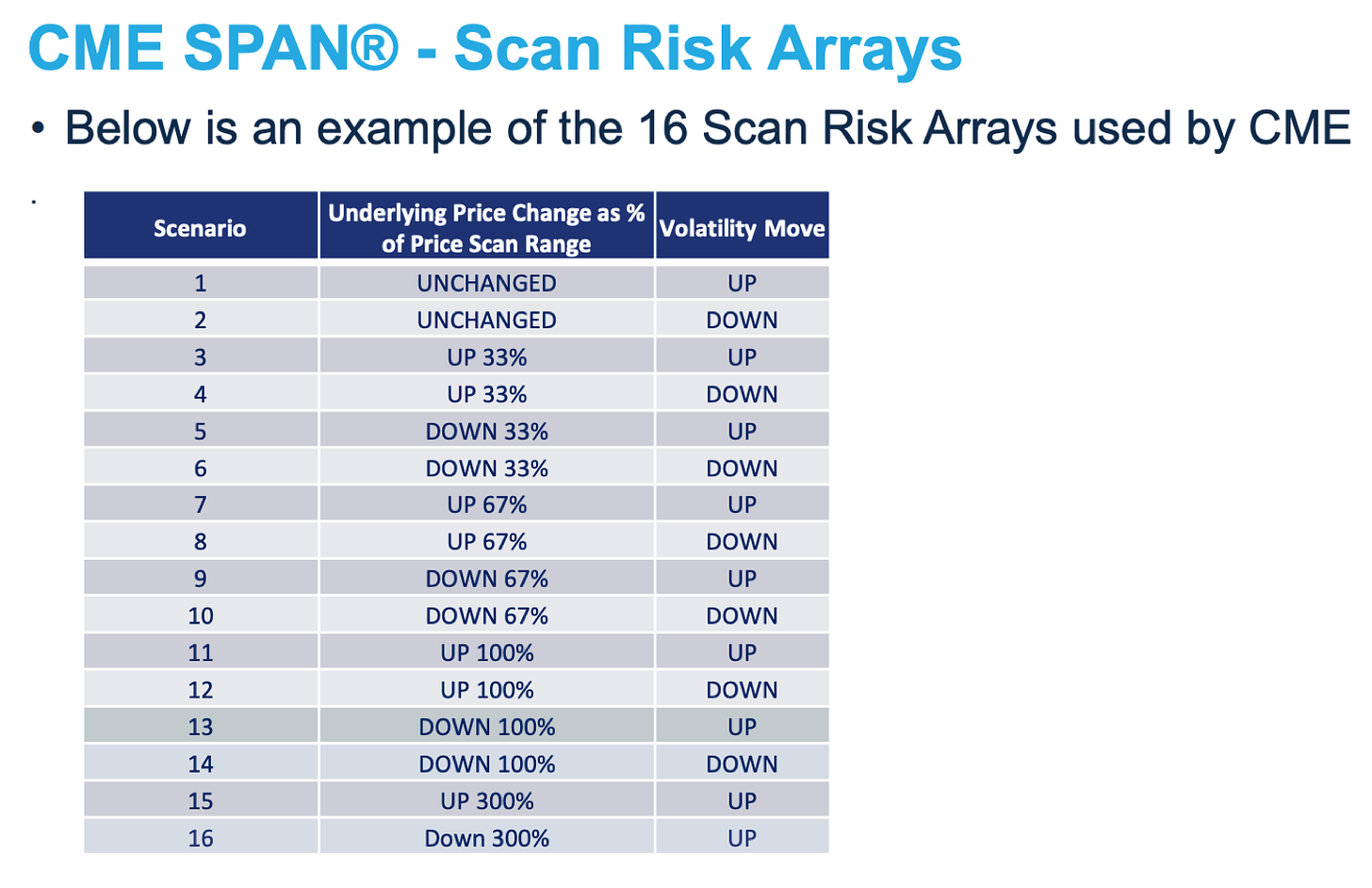

Clearinghouses rely on a number of detailed models to determine how much margin is required across all its users at any point in time. CME’s model is called SPAN (Standard Portfolio Analysis), which it first began using in the 1980s. SPAN calculates the potential returns of a user’s portfolio under a wide range of scenarios, taking into account things like volatility, interest rates, and overall market activity. In the case of your oil trade, CME determined via the SPAN model that $49,500 was all that was needed to open your position given today’s market conditions.

(Source)

These margin models affect trading in predictable ways:

They incentivize spread trading - if traders can offset a long position with a similar short to limit their downside, the clearinghouse normally rewards this with lower margin requirements.

They make adjacent exchange products more attractive - clearinghouses can assess a customer’s risk across multiple trading accounts & asset classes to lower margin requirements. If a trader is active in CME’s oil, US Treasury, and gold futures markets, excess margin in one account can be used to cover other parts of their portfolio if needed. Adding that extra product or trading strategy becomes more efficient as size increases.

They’re used as a policing mechanism - when markets become volatile CME can choose to raise margin requirements in certain products as it deems appropriate. In early 2021 silver prices surged to eight year highs, sparking major volumes & volatility in CME’s silver futures market. CME responded by raising margin requirements nearly 20% overnight, prompting traders to send more money to the clearinghouse or exit their positions altogether. A more infamous example of this policing role came in early 2021, when the DTCC (the world’s largest clearinghouse) made Robinhood cough up an extra $3 billion in margin amid the GameStop meme stonk drama. Clearinghouses use their power as safeguard of last resort to keep markets from becoming dangerously volatile or chaotic.

The Business

We’ve talked about how clearinghouses add value to the economy. We’ve talked about how they perform their basic function & how they oversee markets. How do they act as part of an exchange’s strategy? To answer this, we again return to the $100 million energy trader.

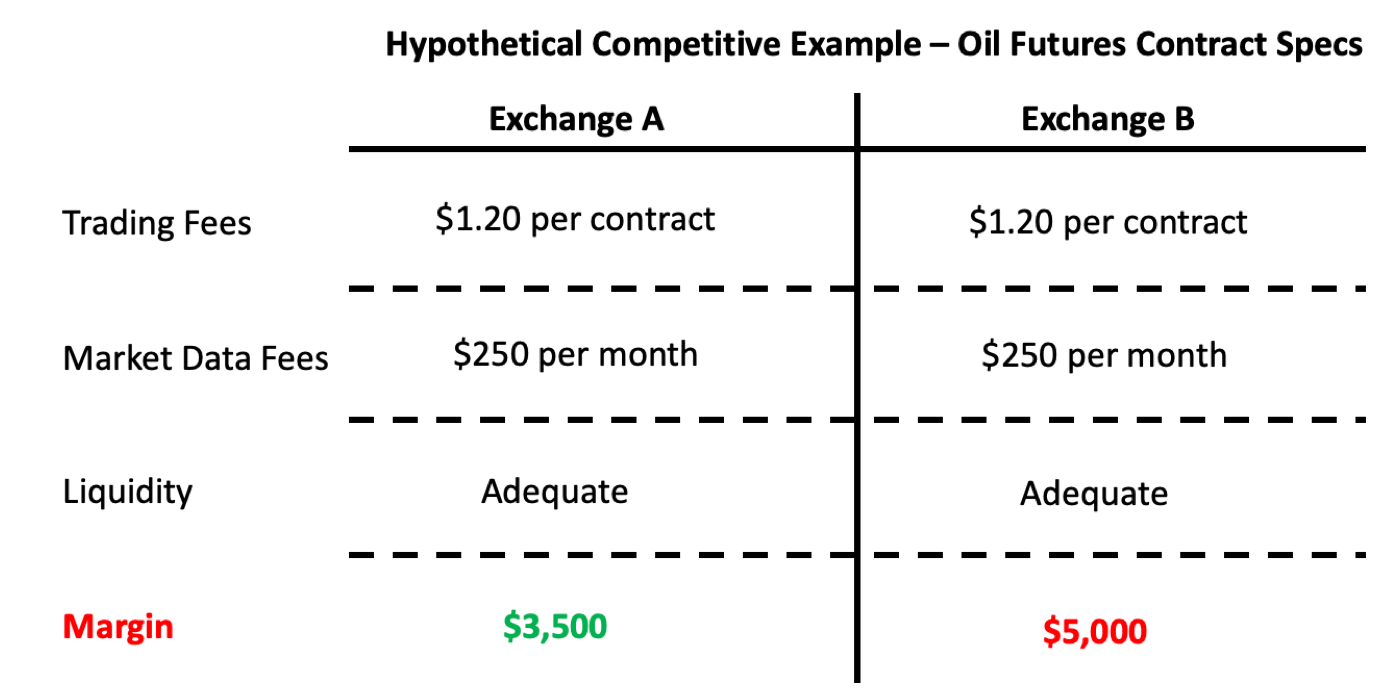

Imagine you’re choosing which exchange to open your oil futures trade - Exchange A and Exchange B. Both charge the same fees for trading & market data and have similar levels of liquidity. But one exchange only requires initial margin of $3,500 for your position, while the other requires $5,000. Because you want to be as capital efficient with your trading as possible, you should choose Exchange A every time:

(Source - author rendering)

How could A open your position for less money than B? Its clearinghouse had a more efficient margin model, meaning it could manage the same amount of risk for less upfront capital.

This is the core game of the clearinghouse business - figuring out how to require as little capital as possible while still acting as a safeguard & maintaining enough buffer to ensure markets are safe. The exchange who perfects their margin model has a massive advantage over competitors and will likely be the one who controls the majority of market share where they operate. Clearinghouses employ armies of math & actuarial PhDs to constantly search for better ways to calculate margin & find that extra advantage over other exchanges. Even small improvements could have a massive impact on an exchange’s value proposition.

Apart from exchange vs. exchange competition, clearinghouses add value to all exchanges across the industry. Their near-spotless reputation as effective risk management systems place them near & dear to regulator’s hearts. The SEC & CFTC love clearinghouses almost as much as I do. They show their love by forcing markets to be centrally cleared whenever possible, especially after the 2008 financial crisis. They did this by outright mandating central clearing and forcing banks to offload inventory, leaving clearinghouses ready to pick up markets where banks left them behind. Clearinghouses have been a major secular catalyst for the exchange industry since 2008 and enhance their structural moats to this day. If more off-exchange markets show signs of systemic risk (like Archegos helped highlight earlier this year), regulators may decide more assets should be centrally cleared, benefitting their exchange owners for even more years to come.

Hopefully my love letter helped convince you how important & fascinating clearinghouses are in their current form. The nature of these networks make it so we don’t hear about them when they’re working. We only get a glimpse into their power & business when markets become too chaotic, like in 2008, or March 2020, or early 2021. Each time, while plenty of traders lose money & go bankrupt, clearinghouses never show signs of collapsing or even breaking a sweat. Their design creates immense trust in global financial markets, and their business helps exchanges compete with each other and excel as an industry. The next time you hear about a derivatives trade, make one yourself, or even on your next coffee break, give clearinghouses a small thought of praise. They helped the economic engine work more for your good than you may have thought possible.

Thank you for reading this issue of Front Month. Word of mouth is the #1 way others find this newsletter - If you liked this week’s content, please consider sharing with friends & colleagues. Questions & feedback can be sent via email or Twitter.

Disclaimer: I am not a financial advisor. Nothing on this site or in the Front Month newsletter should be considered investment advice. Any discussion about future results or projections may not pan out as expected. Do your own research & speak to a licensed professional before making any investment decisions. As of the publishing of this newsletter, I am long ICE, CME, TW, NDAQ and VIRT. I am also long Solana.