Welcome to another issue of Front Month, a newsletter covering the biggest stories in exchanges every Friday. If you have questions or feedback, please reply to this email or find me on Twitter. If you like this newsletter and want to follow the exchange industry with me, please hit the Subscribe button below & be sure to share with friends & colleagues:

We forget how influential Bernie Madoff was at the height of his power on Wall Street.

By the year 2000, Bernie Madoff Investment Securities (BMIS) had amassed over $300 million in assets and was one of the top trading firms in the US. The Madoff family had close ties to regulators including FINRA and the SEC. Bernie himself was Nasdaq’s chairman for a few years in the early 90’s, and his firm was at one point Nasdaq’s largest market maker. Colleagues were often quoted praising the Madoff family - “You couldn't say enough nice things about them… they were just great, great people who would do anything for you”. The rise of a visionary Wall Street firm seemed destined for generational success…

That is, until it all came crashing down after a $65 billion Ponzi scheme was discovered, the largest in history. That story’s for another week.

There were legitimate arms of BMIS - namely, the highly successful market-making business. The firm started out as a penny stock advisory shop in the early 1960s, a time when the SEC was beginning to automate its market data & quotation systems to improve trading. the National Association of Securities Dealers (NASD) was tasked with developing these systems, which would make OTC stocks easier & cheaper to trade, and level the playing field for new market makers like Madoff looking to compete. In those days, brokers were able to quote wide spreads between bids & offers because the market was illiquid and information was scarce. Prices only updated once per day, which gave the top market makers freedom to charge what they wanted for trades. NASD’s goal was to disrupt this & lower costs.

In early 1971, the NASD Automated Quotations system (NASDAQ) was launched, bringing radical transparency to the OTC market. Instead of shopping around for quotes from the top dealers, investors could trade using the best quotes broadcasted through Nasdaq’s system. Market makers shifted from competing on relationships to competing on price & efficiency. Madoff leveraged Nasdaq’s technology to offer cheaper prices & make markets better than his competitors. The business began to grow, but a crowded industry with many firms jockeying for market share made meaningful success challenging.

Once again, new technology combined with de-regulation gave Madoff a chance to compete, this time in the big leagues. In the mid-1970s the SEC became focused on breaking the NYSE’s monopoly on trading of NYSE-listed stocks. Through a series of laws & exchange upgrades, the SEC allowed regional market makers to trade stocks that only Big Board members had access to in the past. Now trading large-cap, liquid stocks, Madoff was again able to win business by competing on efficiency rather than relationships, but this time with an advantage over the competition. BMIS bet big on electronic trading near its infancy, spending millions to build an automated trading & market making system. When the project was finished, Madoff’s firm could fill orders 9x faster than an NYSE specialist - a huge head start.

Imagine two stockbrokers receive client orders to trade shares of General Electric - one wants to buy 100 shares, the other wants to sell 100 shares. These brokers would route the business to a market maker who could either fill the order first, at the best price, or both. Madoff’s state of the art system would be the first to buy GE from the selling broker at the bid price of, let’s say, $50, and sell those shares to the buying broker at the ask price of $51, collecting a near risk-free $1 per share profit before slower specialists knew what had happened.

Being one of the fastest market makers in town came with significant power, and it allowed Madoff to invent a new sales tactic to win even more trades: paying brokers for order flow. Now, instead of collecting GE’s full bid/ask spread in the previous example, Madoff might choose to pay $.05 per share to each broker for the right to execute their trades. While cutting the trade’s profit from $1 to $0.90 per share, it would entice enough extra volume to Madoff’s market that new revenue would offset the broker rebate. For many brokers, the pitch was a no-brainer - either route orders to the NYSE and be forced to pay exchange & specialist fees, or get paid to route to Madoff. By the end of the 1980’s, Madoff’s firm handled an impressive 5 million shares per day, or ~2% market share in NYSE-listed securities.

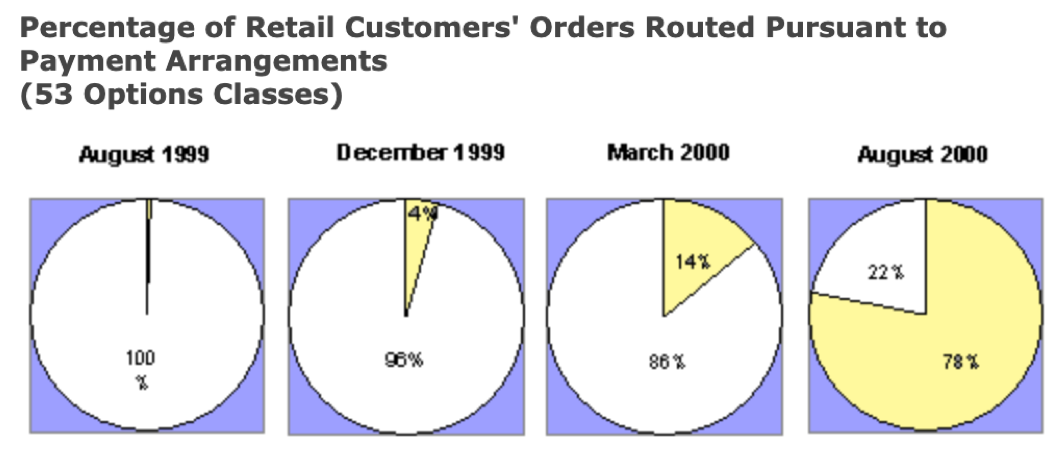

Madoff’s new payment for order flow (PFOF) strategy began to catch on with competitors as brokers looked for ways to cut costs, but it didn’t come without controversy. Wouldn’t these payments distract market makers from quoting better prices? Would this raise conflicts of interest for the brokers who could prioritize kickbacks over giving clients the best price? As PFOF popularity rose, the SEC began to investigate. Each time regulatory opinions were given, the practice of payment for order flow was allowed to continue, although with strict disclosures by participating brokers. Why? Because it fostered exchange competition. PFOF allowed firms like Bernie Madoff’s to take business & power away from the NYSE and push the exchange to find new ways to keep market share, something the SEC has been looking to do for decades. With a tentative blessing from regulators, payment for order flow quickly overtook the stock market & spread to the options market as well. In August 1999, less than 1% of retail options orders involved payment for order flow. By August 2000, 78% involved PFOF:

(Source)

In the end, Madoff’s market making business faded after bid/ask spreads & profits shrank and algorithmic trading became popular in the mid-2000s. Even though the business is now defunct and its creator in jail, payment for order flow remains an omnipresent & controversial topic in today’s markets, normally spoken in tandem with one discount broker in particular - Robinhood. We all know Robinhood, the free trading app with an addictive UI, free stock, and more than 13 million mostly retail users. The Silicon Valley broker is working towards a potential 2021 IPO with a valuation as high as $20 billion. A big piece of this valuation relies on a unique part of their business - market makers pay more money per order to Robinhood than any other broker in the industry.

What’s so special about Robinhood’s order flow? To answer this, let’s put ourselves back in Bernie Madoff’s shoes. This quote from an old Trader’s Magazine article says it best:

“Madoff's business plan was simple: Accept orders only in the biggest, most liquid stocks from ‘uninformed’ retail investors. Charge no fees. Guarantee fills on all orders up to 3,000 (later, 5,000) shares. Execute orders faster than the New York Stock Exchange.”

(Source)

‘Uninformed’?! How dare you!

It does make sense, though. Market makers place more value on retail orders in liquid stocks because those orders are less risky to trade against. In exchange for profiting from a stock’s bid/ask spread, market makers take on some risk of the market moving against them. Institutional ‘informed’ traders know when market imbalances will cause wild short term price swings because they have access to market data that retail traders don’t. Because of this, it’s harder to profit consistently off institutional order flow. Retail traders won’t run away when the order book tips out of balance.

Is payment for order flow a “good” thing? I have no idea. PFOF is a legal practice that helps market-makers and brokers compete with exchanges for volume. It’s been around for decades and has not been banned by the SEC. It is however a highly scrutinized, abstract part of the market that is met with swift punishment when abused. As Robinhood’s IPO inches closer to reality, the debate over payment for order flow is bound to only grow louder.

I like to think that, sitting in his Butner North Carolina prison cell, Bernie Madoff overhears a news report on TV mentioning payment for order flow, and a sly smirk crosses his face knowing his invention not only lives on, but thrives.

BlackRock’s Crypto Tiptoe

In a filing on January 20, BlackRock updated prospectuses for two funds to include Bitcoin futures among the list of assets they’re allowed to buy. The funds have combined AUM of ~$60 billion and invest in a wide range of securities including equities, fixed income, real estate, and alternative assets like CDOs and now, Bitcoin.

While BlackRock hasn’t revealed which exchange they’d use to execute their Bitcoin futures trades, CME is the only CFTC-registered exchange offering a cash settled product - it’s likely they’ll be the venue of choice.

This could be a huge deal for CME, BlackRock, and Bitcoin. Due to a lack of classic fundamental metrics to value Bitcoin, investors focus on two things to help predict price: demand and access. The demand side of the equation is as high as ever - wanton global stimulus & improving crypto infrastructure has fueled a boom in retail & institutional Bitcoin interest. Access has always been the slower moving driver of price, given the market’s disdain for managing crypto wallets & the SEC dragging its feet on approval of a Bitcoin ETF. Interest growing from the largest asset manager in the world - with more alumni staffing parts of Biden’s administration - could materially improve the outlook for a Bitcoin ETF. Access granted.

For CME, a Bitcoin ETF that uses futures to hedge exposure would give their crypto product a new & highly profitable use case. For a futures market to be more than just market makers trading with each other, commercial traders need to have a reason to hedge price risk of an underlying asset, and be willing to pay for this hedging ability. In the oil markets, global producers like Chevron & Exxon would be considered commercial traders. Who are commercial traders when it comes to Bitcoin? If BlackRock enters the Bitcoin futures market in any size, they would be a top commercial user & paying customer of CME’s relatively young crypto market.

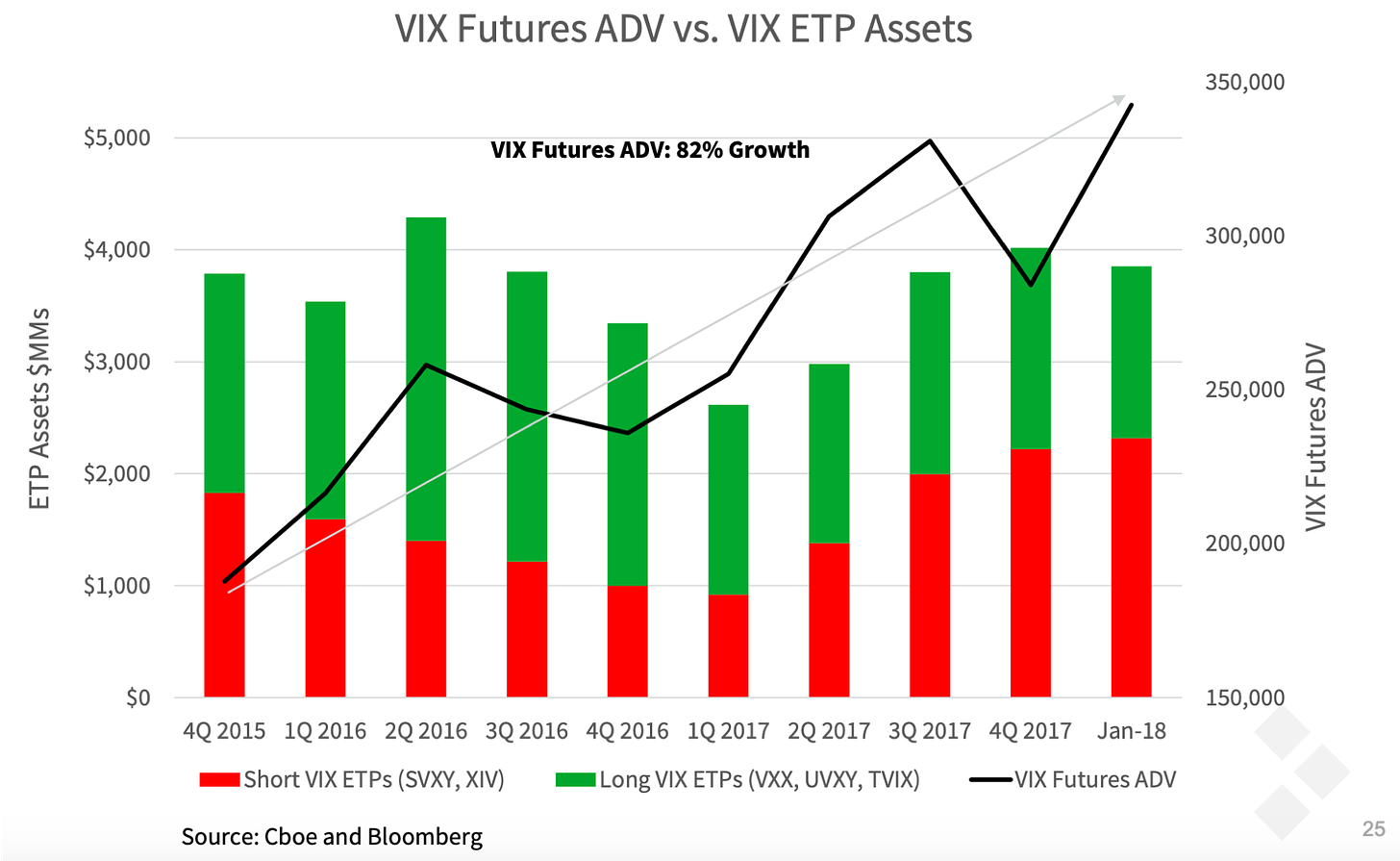

I’ll reference one more example to drive this opportunity home - the direct relationship between volatility ETP activity and CBOE VIX futures volume. Volatility ETPs give holders their desired exposure via rolling positions in CBOE VIX futures contracts - more assets in these ETPs means more demand for futures contracts that need to be traded. When this trend is playing in CBOE’s favor, management loves to prominently display it in earnings decks (like Q4 2017’s). When it’s not a driver of volume growth like we’ve seen since February 2018’s VIX-splosion, charts like the below are nowhere to be found…

Just as VIX ETPs are a big driver of CBOE’s volumes, Bitcoin ETFs could become a big driver of CME volume. I’m watching updates in this area closely for clues about BlackRock’s next move & what the impact could be to trading volumes down the road.

Honorable Mentions

Big banks including JP Morgan, Citigroup, Morgan Stanley, and Goldman Sachs reported Q4 2020 results that largely beat analyst expectations on the back of strength in their respective trading units. JP Morgan’s trading revenue surged +29% in 2020 driven by - in their words - “strong performance in Credit, Currencies & Emerging Markets, Commodities, Derivatives and Cash Equities”. Quite literally every tradeable asset made money. Banks are among the top customers of exchanges, so good times for bank trading desks normally trickles down to the exchanges that helped facilitate their success.

The FT reported on January 19 that the London Metal Exchange is planning to close its 144 year old physical trading floor, “The Ring”. LME’s floor was the last open outcry venue in Europe, known for its strict dress code and bright red sofa.

Chart of the Week

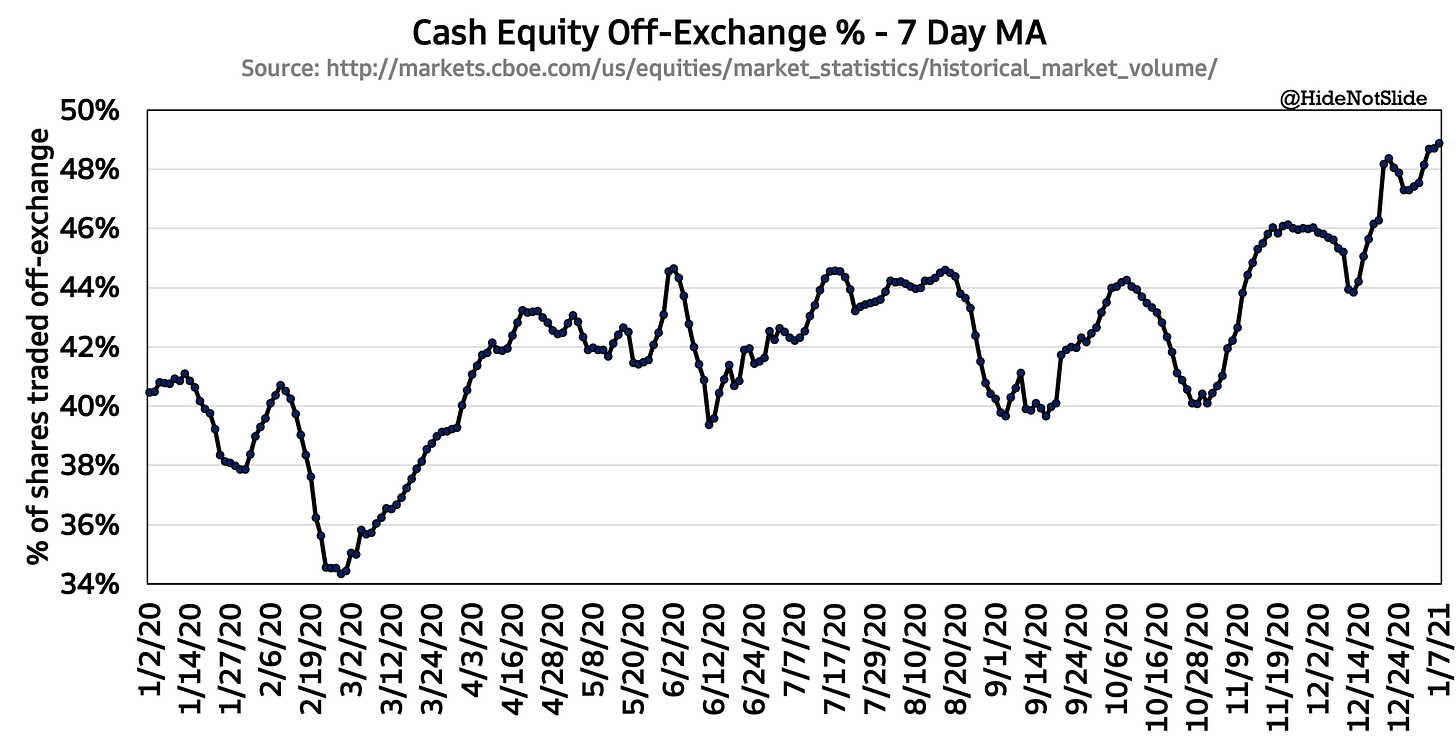

An on-topic chart this week - despite historically high cash equity volumes through 2020 and 2021 YTD, we’re quickly approaching a market where more shares trade off-exchange than on.

Some of this is due to the above PFOF dynamic - market makers like Virtu, Citadel Securities and others are able to offer brokers lower execution costs than exchanges can in many cases. Intense competition among a growing number of exchanges could be another driver. When new entrants like MEMX and MIAX PEARL enter the market, they take volume away from the legacy exchanges and make the group as a whole less liquid. A few super liquid off-exchange venues look better and better compared to a crowded, stretched field of exchanges fighting for market share…

Will this trend continue? No one really knows. If retail traders keep growing their presence in the market, my guess is off-exchange share will continue to rise. This chart doesn’t mean the legacy exchanges are making less money - in fact the opposite is true. It does mean that incremental volume that has come into the market is increasingly going off exchange; to the extent that new trading stays around, exchanges could soon find themselves trading a minority of total market volume.

Thank you for reading this issue of Front Month. Word of mouth is the #1 way others find this newsletter - If you liked this week’s content, please consider sharing with friends & colleagues. Questions & feedback can be sent via email or Twitter.

Disclaimer: I am not a financial advisor. Nothing on this site or in the Front Month newsletter should be considered investment advice. Any discussion about future results or projections may not pan out as expected. Do your own research & speak to a licensed professional before making any investment decisions. As of the publishing of this newsletter, I am long ICE, CME, CBOE, NDAQ and VIRT. I am also long Bitcoin.